Brenda Power:

The Catholic Church has hidden behind bureaucracy and rhetoric for far too long, it’s time for legal intervention

The Sunday Times Published: 24 July 2011

If Enda Kenny had squirted shaving foam into a paper plate and flung it all over the papal nuncio’s soutane, he wouldn’t have caused any more astonishment than he did with that speech on Wednesday.

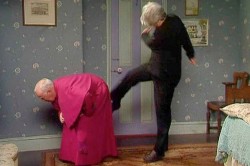

The silence from the Vatican ever since is reminiscent of Bishop Brennan’s stunned disbelief in the episode of Father Ted in which the bishop is invited to bend over and inspect a skirting board and then kicked up the backside. One of these nights, I imagine, the Pope will sit bolt upright in his gilded bedchamber and cry: “He did! He did call me narcissistic, elitist and dysfunctional, the little bollix!”

The taoiseach’s speech has been hailed as a final, irredeemable severing of church and state in Ireland, a reclamation of our sovereignty. It’s also been termed hysterical and ill-judged, a populist outburst of radio phone-in invective that glossed over the state’s failures on child protection.

It was certainly unprecedented. It is rare to hear any politician criticise a mainstream religious institution. But when the political leader is Irish and the institution is the Catholic church, then it becomes what mathematicians term a “10-sigma event”. In other words, if the life of the universe was repeated one billion times over, the chance of an Irish taoiseach denouncing the Vatican would still be theoretically unlikely.

At least that’s what the Vatican must have calculated. Otherwise, it might have shown our civil laws and the welfare of our vulnerable citizens a little more respect before now.

The consensus on Kenny’s speech seems to be that some straight talking from an Irish government to the Vatican was about half a century overdue. Cynics may argue that Kenny’s initiative is not so much a measure of how confident the Irish state has grown, but a reflection of how weakened the Catholic church has become.

The immediate response of the papal nuncio was to express his surprise at the severity of Kenny’s attack given that the taoiseach appeared to be demanding of canon law a standard of child protection that does not exist in civil law. It is more than 13 years since Bertie Ahern promised to make mandatory the reporting of information regarding the abuse of children, and yet Kenny was still promising it last Wednesday.

In this regard, any politician with a Dail career as long as Kenny’s is vulnerable. And it’s not just in relation to clerical child abuse that some straight, honest dealing is overdue. The torture meted out by a Roscommon traveller woman to her eight children in 21st century Ireland suggests there are still categories of perpetrator and victim who are shielded by their singular status from the reach of civil and social mores.

Last weekend, Brian Walsh, a Fine Gael TD, suggested the abuse of those children may have gone unchecked for so long because they were travellers. Walsh is almost certainly right about that, but not for the reasons he suggested. If a blind eye was turned to the woman’s behaviour it was not because of official indifference to her children’s plight, but rather because the fear of appearing to be critical of “traveller culture” might have rendered social workers, teachers or gardai slow to intervene. Persistent child abuse, ranging from the denial of an education to exposure to drugs, alcohol and violence, to the infliction of a dead-end lifestyle upon innocent youngsters, is endemic in the travelling community and yet no politician has the guts to say so. The Pope is a comparatively low-risk target.

Whenever the Vatican does get around to responding we can expect more hair-splitting pedantry of the kind that characterised the papal nuncio’s initial reaction. There will be grave dissertations on the distinctions between guidelines and directives, advice and instructions. The reason why Kenny’s speech struck such a chord is that most ordinary folk have long since wearied of the church’s linguistic and procedural contortions designed to confuse this simple issue.

The truth is that we’ve known for years that the Catholic church covered up instances of child abuse, and that this concerted policy can only have come from the top. This newspaper revealed how Cardinal Seán Brady once participated in a meeting in which a child abuse complainant was sworn to secrecy. If, as the Russian proverb has it, a fish rots from the head down, then we can assume the bishops who moved offending priests to fresh pastures were simply complying with the spirit of that dictum.

The letter of the law, both canon and civil, has for too long offered a refuge to persons of responsibility in search of a handy escape clause. It shouldn’t matter whether the Vatican’s 2001 guidelines for the reporting of abuse had an advisory or an imperative status. Functioning human beings don’t need legal texts to tell them a child-abuser needs to be stopped. Nor do they need directives telling them that if a child is in danger from an adult in a position of trust or care, they have a duty to intervene. For too long, certain categories of people have been able to manipulate deference and special pleading to exempt themselves from moral and social obligations.